You By Will Hall, Message Editor

ALEXANDRIA (LBM)—Southern Baptist history is complicated. Slavery is most often cited as the cause for the split from Northern Baptists that led to the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention, and it was a decisive factor.

However, Southern Baptists also strongly disagreed with Northern Baptists regarding how they were organized as the General Missionary Convention of the Baptist Denomination in the United States of America for Foreign Missions (also known as the Triennial Convention). In general, Southern members preferred a more centralized structure of operating while Northern members favored the formation of independent societies for home missions, foreign missions and the publication of tracts, according to historian Robert A. Baker.

Likewise, Baptists in the South felt they were not being treated equitably in the appointment of home missionaries to the region.

But, the records of the first SBC annual meeting indicate the final straw was the approval by the Board of the Triennial Convention, in a Boston meeting, of a new rule that prohibited slave owners from serving as foreign missionaries.

W.B. Johnson, the first SBC president, perceived the action not in terms of acknowledging the sin of slavery but as interference in the rights of Southern Baptists to evangelize the nations. In an address he penned on behalf of the newly formed SBC, Johnson denounced the new rule, writing, “THEY WOULD FORBID US TO speak unto THE GENTILES.”

Yet, despite the disquieting association with slavery in its origins, the Southern Baptist Convention has had a remarkable history of leading the country in racial reconciliation.

Indeed, Johnson himself indicated the fervor with which Southern Baptists shared the Gospel overseas.

But they also preached the message of John 3:16 fervently in the pulpits of the Deep South, and it was transforming spiritually and socially, replacing racial hatred with compassion for Blacks, then motivating outright opposition to slavery and racism.

Even in breaking with the Triennial Convention in 1845, Southern Baptists declared their resolve that “the Board of Domestic Missions be instructed to take all prudent measures, for the religious instruction of our colored population.”

Moreover, historian David L. Chappell noted that after the 1954 landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, “the Southern Baptist Convention overwhelmingly passed resolutions supporting desegregation and calling on all to comply with it peacefully.”

He also documented that “[b]y 1958 all SBC seminaries accepted Black applicants.”

But, between 1845 and 1954, Southern Baptists took multiple steps to atone for their part in the racial division of our country – even allocating the equivalent of a quarter of a million dollars in 1886 (just two decades after the South’s economy had been wrecked by the destruction of war) “to aid young colored ministers in acquiring education and more perfect training for their work.”

Moreover, after the 1950s, Southern Baptists continued to set the pace for religious groups in bettering U.S. race relations, and are yet pursuing initiatives such as intentional inclusion of ethnic minorities on committees and in leadership positions, as well as increasing the number of predominantly ethnic congregations (by invitation to established congregations and through planting churches in ethnic communities).

TIMELINE

1884 Southern Baptists passed the “Resolution on Colored People,” which acknowledged the “peculiar claims” upon them of the “seven millions of colored people within the bounds of this Convention” regarding religious instruction “for their evangelization, and their proper instruction in the truths and duties of the Gospel”; and, asked the Home Mission Board to raise up properly instructed “colored preachers and deacons.”

1886 Just two years later, in another “Resolution on Colored People,” Southern Baptists asked the Home Mission Board to spend $10,000 (the equivalent of a quarter of a million dollars in 2017) “to aid young colored ministers in acquiring education and more perfect training for their work” — just two decades after the South’s economy was wrecked by the destruction of war.

1939 The SBC adopted the “Resolution Concerning Lynching and Race Relations,” repudiating lynchings and “all forms of mob violence.” Moreover, Southern Baptists lamented “the disproportionate distribution of public school funds, the lack of equal and impartial administration of justice in the courts, inadequate wages paid for Negro labor and the lack of adequate industrial and commercial opportunity for the Negro race as a whole” and messengers pledged “as Christians and citizens to use our influence and give our efforts for the correction of these inequalities.”

1940 Messengers passed the “Resolution on Race Relations,” pledging to “strive to the end that our friends and neighbors of the Negro race shall have in all instances, equal and impartial justice before the courts, better and more equitable opportunities in industrial, business and professional engagements; and a more equitable share in public funds and more adequate opportunities in the field of education.”

1941 Southern Baptists adopted the “Resolution Concerning Race Relations” that reaffirmed “our deep and abiding interest in the welfare of all races of mankind, and particularly our deep and abiding interest in the welfare and advancement of the Negro race, which lives in our midst to the number of some ten or eleven millions” and urged “the pastors and churches affiliated with the Convention, and all our Baptist people, to cultivate and maintain the finest Christian spirit and attitude toward the Negro race, and to do everything possible for the welfare of the race, both economic and religious and for the defense and protection of all the civil rights of the race”; and, condemned mob lynchings, calling for “the creation and maintenance of law and order and for the suppression of all mob violence throughout our land.”

1942 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary began offering night classes for black preachers on its campus.

1942 Southern Baptist Theological Seminary began teaching black students on its campus in a “Negro Extension Department,” separately from whites, in vacant faculty offices.

1944 Southern Baptist Theological Seminary faculty granted Garland Offutt a degree in 1944, making him the first black graduate of any SBC seminary.

1946 The “Resolution on Race” declared the SBC “repudiates, and urges the members of the churches of the Convention to refrain from association with all groups that exist for the purpose of fomenting strife and division within the nation on the basis of differences of race, religion and culture.”

1950 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary trustees voted to admit African American students.

1951 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary admitted African American students as candidates for the B.D., Th. M. and Th. D. degrees.

1951 The African American Community Baptist Church in Santa Rosa, California, was voted into the Redwood Empire Southern Baptist Association, becoming the first African American congregation to join the SBC.

NOTE: Predominately Black churches number more than 4,000 in the SBC, now.

1955 Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary granted degrees to its first two African American graduates.

NOTE: “By 1958 all SBC seminaries accepted Black applicants,” Chappell noted in “A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow.”

1959 The “Resolution on Meeting with National Baptist Negro Leaders” called for SBC leaders to meet with their counterparts at the “two National Conventions of Negro Baptists.”

1961 Southern Baptist Theological Seminary hosted civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. on campus.

1961 Messengers approved the “Resolution on Race Relations,” reaffirming Southern Baptists’ “conviction that every man has dignity and worth before the Lord” and pledging to “commit ourselves as Christians to do all that we can to improve the relations among all races as a positive demonstration of the power of Christian love.”

1965 The SBC adopted the “Resolution on Human Relations,” apparently in support of the Civil Rights Act, stating “in the spirit of Christ to a ministry of reconciliation among all men … that all men stand as equals at the foot of the cross without distinction for color … to provide positive leadership in our communities, seeking through conciliation and understanding to obtain peaceful compliance with laws assuring equal rights for all …. pledge ourselves to go beyond these laws in the practice of Christian love.”

1968 “A Statement Concerning The Crisis In Our Nation” called for an end to segregation and encouraged Southern Baptists to work toward “equal opportunities in public services, education and employment.”

1970 Only 19 years after the first African American congregation was received into the SBC (California), church growth expert C. Peter Wagner declared the SBC “the most ethnically diverse denomination” in the United States of America.

1972 Herbert Cotton (Alaska) is elected the first Black president of a state convention of Southern Baptists.

1986 Southern Baptist Theological Seminary hired T. Vaughn Walker, the first African American professor at any SBC seminary.

1987 Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary (Now Gateway Baptist Theological Seminary) hired Leroy Gainey, the second African American professor of an SBC seminary.

1989 Richard Land, executive director of the Christian Life Commission (now the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission), called on Southern Baptists “to urge their agencies and institutions to seek diligently to bring about greater African American representation at every level of Southern Baptist institutional life.”

1992 A multi-ethnic advisory study group, appointed by SBC President Ed Young, recommended ethnic minorities be added to every board, committee, and commission as well as placed on the annual meeting program; and, it urged the formation of an “Ethnic and Black Task Force” to help Southern Baptists engage all races in sharing the Gospel.

1995 The SBC passed a “Racial Reconciliation” resolution, apologizing for the role Southern Baptists played in the wrong of racism.

NOTE: Southern Baptists were the first major Christian group to take such action. In 2000, the United Methodist Church took similar action, and many Catholic dioceses also issued public apologies as part of The Great Jubilee year, a traditional time for atoning.

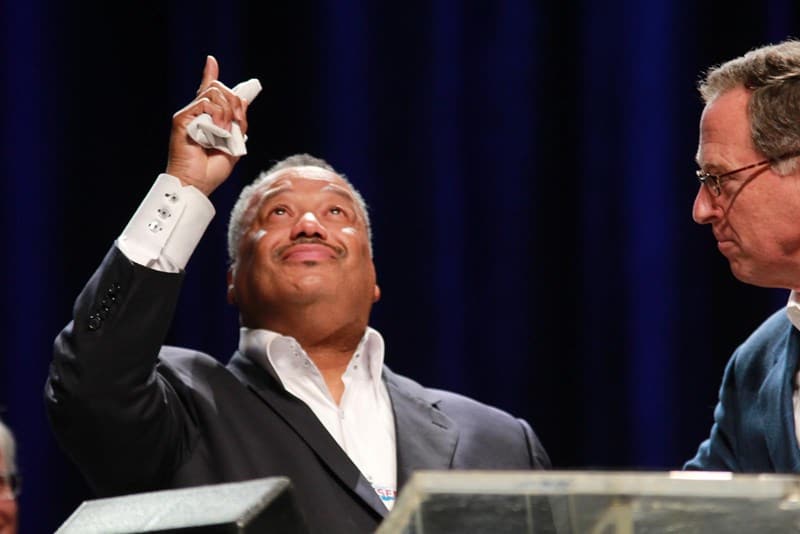

2012 Messengers overwhelmingly elected Fred Luter, pastor of the 5,000-member Franklin Avenue Baptist Church in New Orleans, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, and so he became the first African American to lead the denomination.

2016 The resolution “On Sensitivity And Unity Regarding the Confederate Battle Flag” was adopted, calling for “our brothers and sisters in Christ to discontinue the display of the Confederate battle flag as a sign of solidarity of the whole Body of Christ, including our African American brothers and sisters.”

2017 In Phoenix, the SBC passed the resolution “On the Anti-Gospel Of Alt-Right White Supremacy” which decried “every form of racism, including alt-right white supremacy, as antithetical to the Gospel of Jesus Christ,” denounced and repudiated “white supremacy and every form of racial and ethnic hatred as a scheme of the devil intended to bring suffering and division to our society,” and acknowledged “that we still must make progress in rooting out any remaining forms of intentional or unintentional racism in our midst.”