By Gary D. Myers, NOBTS Communications

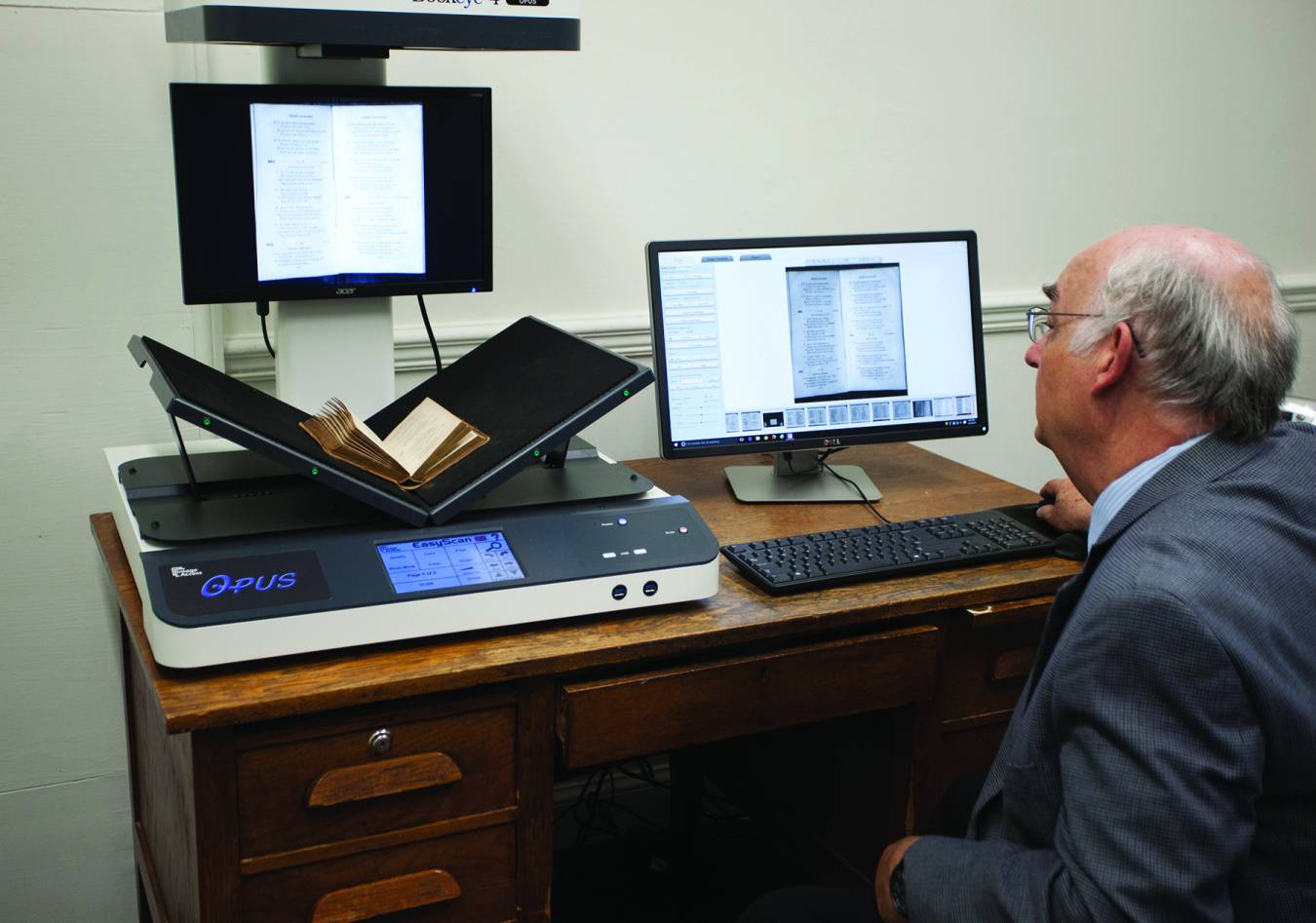

NEW ORLEANS – The musty smell of antiquity fills the air as music professor Ed Steele positions an old leather-bound book on an odd-looking scanner.

With the press of a button the scanner comes to life, a light passes over the page, and before long a scanned page appears on Steele’s computer screen.

Steele, a faculty member at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary’s Leavell College, spent much of his recent sabbatical scanning and digitizing page after page from rare hymnals. To date, he has scanned and digitized nearly 30 of the seminary’s 400-plus rare hymnals and a few hymnbooks from private collections.

The digitized hymns are available in Adobe PDF format free of charge at the seminary’s online home for the new Center for Hymnological Research: http://www.nobts.edu/library/hymnological-research.

“Because of their condition and their age, although we have them, the rare hymnals are not usable, or available or accessible,” Steele said, pointing to a shelf full of rare hymnals. “Now the accessibility comes from this scanner.”

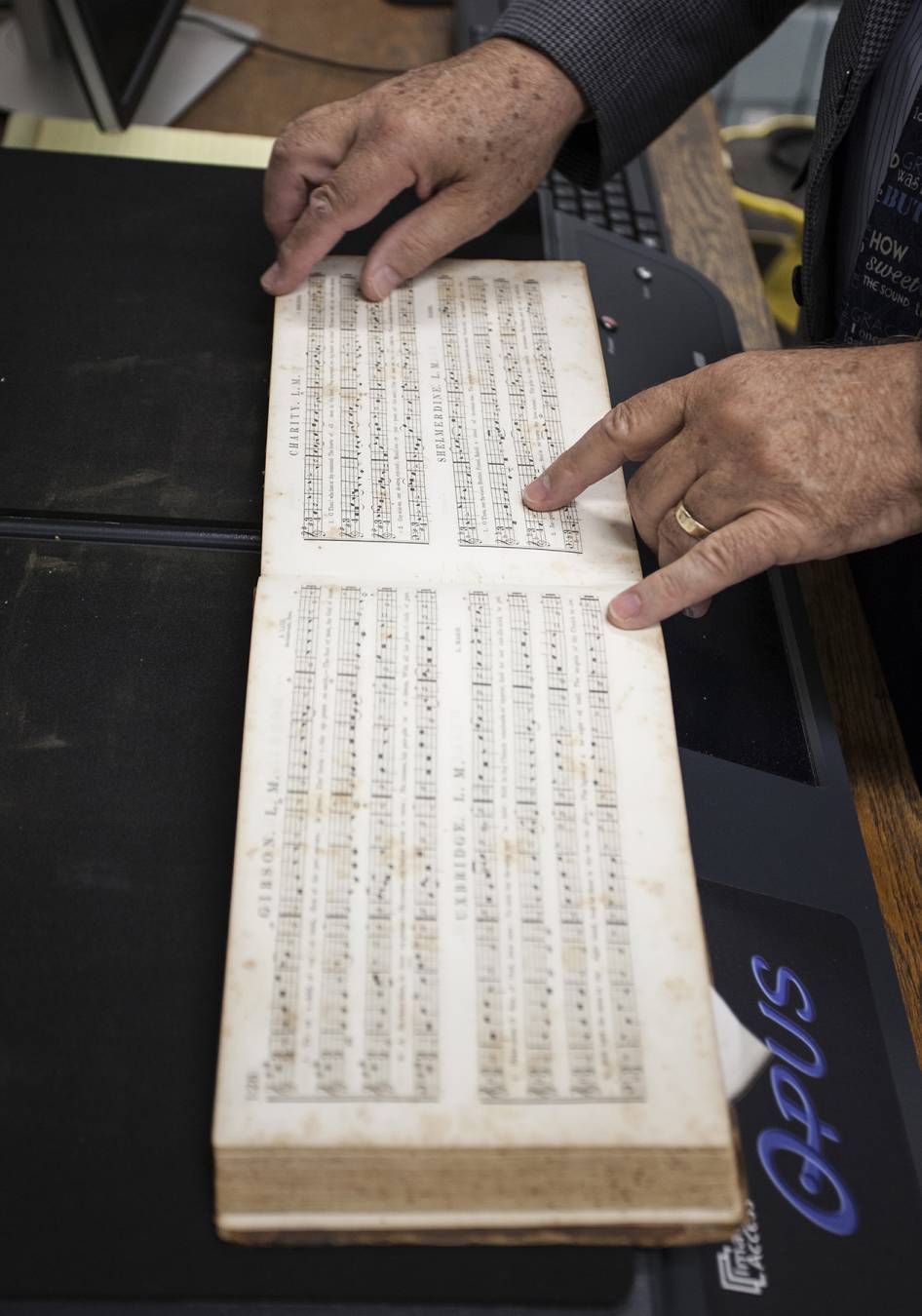

Leavell College professor Ed Steele prepares an early “tune book” for scanning. Tune books, which appeared in the 1830s, were among the first books to include music notes. Earlier hymnals included only the text of the hymn

The Martin Music Library at NOBTS holds more than 5,000 hymnals which were donated by Edmond Keith, a layman who loved hymnody. Most of the rare hymnals in the music library are a part of the Edmond Keith Collection — some dating to the early 1700s. Others were obtained through the efforts of Harry Eskew, who taught hymnology at the seminary for 36 years.

While many of the hymnals in the Keith Collection can be checked out and studied, access to the rare hymnals has been limited. The rare hymnals are stored in a climate and humidity controlled rare book room. Limited access is required to preserve the fragile physical copies, with meticulous care required when handling them.

The 1713 “Hymns in Commemoration of the Sufferings of Our Blessed Saviour Jesus Christ, Compos’d for the Celebration of his Holy Supper” by Joseph Stennett is among the oldest Steele has digitized so far. Another notable: “A Collection of Hymns, for the Use of the People called Methodists” compiled by John Wesley from 1780. Throughout the collection of rare hymnals, the songs of Isaac Watts and John and Charles Wesley often appear. Digital copies of numerous early Baptist hymnals also are available on the center’s website.

“We’ve had a few scholars who would fly in because they knew what we had … a treasure trove hidden from the world,” Steele said. “Because these are rare, they have not been available to the public. What we are doing is making them available.”

Without the proper equipment, scanning and digitizing a rare book can be a difficult challenge. A person can accomplish the task with a traditional flatbed scanner and basic software, but the process is inefficient, time-consuming and risks damaging the fragile book. New scanning technology provides automation which speeds up the process. Regardless of the innovation, scanning a book is still time-consuming — accomplished by scanning one two-page “spread” at a time.

The new NOBTS scanner, an Opus FreeFlow Bookeye 4 with specialized software, is designed to accommodate even the most fragile books. The high resolution scans preserve the text of the hymnals with stunning detail.

The adjustable platform can be used to scan an open book lying flat or at a v-shaped angle to accommodate a book with a fragile spine which will not open completely. The software automatically corrects skewed portions of the scan regardless of the position of the book. After scanning each two-page spread, the software merges all the scanned files into one PDF document which is ready to be uploaded to a webpage.

With music so deeply entwined in most churches’ Sunday worship, it is hard to believe how recently hymns entered the church. According to Steele, reformers like John Calvin only allowed the singing of Psalms, and many congregations for nearly 100 years sang only from these “psalters.” Benjamin Keach, a Baptist pastor in England, first promoted hymn singing in 1675.

Isaac Watts, born in 1674, began writing hymns as a teenager, and he faced bitter criticism when he began promoting hymns. Steele believes that it was the quality of Watts’ writing that eventually led to wider acceptance of hymns in church. Hymns by Watts, and the Wesley brothers were among the first to be published. Later, George Whitfield brought the hymns of Watts to America during his “Great Awakening” revivals in the mid-1700s. The earliest hymn books did not include music, only the text.

As hymn singing spread in America, publishers began producing “tune books” like the Sacred Harp in the 1830s to teach singing in rural areas of the South, Steele said. Many of the songs used in the great revivals of the 1800s in Kentucky were from these collections. The tune books utilized many of the Watts hymns set to “shape notes.” The Southern and Western Pocket Harmonist and The Southern Harmony are among a number of rare shape-note tune books Steele has digitized. The tune books were among the first books to include music along with the text of hymns.

Scanning the seminary’s rare hymnal collection will be an ongoing, long-term effort, Steele said. Some might say a labor of love. In fact, Steele believes scanning the rare hymnals currently in the NOBTS library will stretch beyond his career into the next generation of music professors at NOBTS.

“One advantage of the scanner,” Steele added, “is the possibility of scanning other collections loaned from individual private collections. My desire is that the Center for Hymnological Research would become a resource for the collection of these rare hymnals and to provide an opportunity for others to make their collections available digitally to the research community.”